What Is The Geographic Term For A Plant And Animal Community Covering A Large Land Area

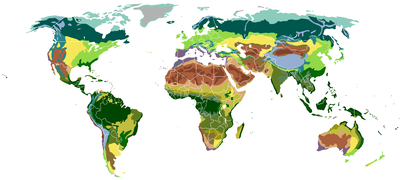

These maps show a scale, or index of greenness, based on several factors: the number and type of plants, leafiness, and plant health. Where foliage is dense and plants are growing quickly, the index is loftier, represented in nighttime green. Regions with sparse vegetation and a low vegetation index are shown in tan. Based on measurements from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra satellite. Areas where there is no data are gray.[one]

Vegetation is an assemblage of plant species and the ground cover they provide.[2] It is a general term, without specific reference to particular taxa, life forms, structure, spatial extent, or any other specific botanical or geographic characteristics. It is broader than the term flora which refers to species limerick. Perhaps the closest synonym is plant customs, but vegetation can, and often does, refer to a wider range of spatial scales than that term does, including scales as large as the global. Primeval redwood forests, littoral mangrove stands, sphagnum bogs, desert soil crusts, roadside weed patches, wheat fields, cultivated gardens and lawns; all are encompassed by the term vegetation.

The vegetation type is defined past characteristic ascendant species, or a common aspect of the assemblage, such as an elevation range or environmental commonality.[3] The gimmicky use of vegetation approximates that of ecologist Frederic Clements' term world cover, an expression withal used past the Bureau of Country Management.

History of definition [edit]

The distinction betwixt vegetation (the general appearance of a community) and flora (the taxonomic composition of a community) was showtime made by Jules Thurmann (1849). Prior to this, the 2 terms (vegetation and flora) were used indiscriminately,[iv] [five] and still are in some contexts. Augustin de Candolle (1820) also made a similar stardom, but he used the terms "station" (habitat type) and "dwelling" (botanical region).[six] [vii] Later, the concept of vegetation would influence the usage of the term biome, with the inclusion of the beast element.[8]

Other concepts like to vegetation are "physiognomy of vegetation" (Humboldt, 1805, 1807) and "formation" (Grisebach, 1838, derived from "Vegetationsform", Martius, 1824).[five] [9] [10] [11] [12]

Parting from Linnean taxonomy, Humboldt established a new scientific discipline, dividing plant geography betwixt taxonomists who studied plants as taxa and geographers who studied plants as vegetation.[xiii] The physiognomic arroyo in the study of vegetation is common among biogeographers working on vegetation on a world scale, or when at that place is a lack of taxonomic knowledge of someplace (eastward.g., in the tropics, where biodiversity is normally loftier).[xiv]

The concept of "vegetation blazon" is more cryptic. The definition of a specific vegetation blazon may include not merely physiognomy but besides floristic and habitat aspects.[xv] [sixteen] Furthermore, the phytosociological approach in the study of vegetation relies upon a cardinal unit, the plant association, which is divers upon flora.[17]

An influential, clear and simple classification scheme for types of vegetation was produced by Wagner & von Sydow (1888).[18] [19] Other important works with a physiognomic approach includes Grisebach (1872), Warming (1895, 1909), Schimper (1898), Tansley and Chipp (1926), Rübel (1930), Burtt Davy (1938), Beard (1944, 1955), André Aubréville (1956, 1957), Trochain (1955, 1957), Küchler (1967), Ellenberg and Mueller-Dombois (1967) (see vegetation classification).

Classifications [edit]

Biomes classified past vegetation

There are many approaches for the classification of vegetation (physiognomy, flora, ecology, etc.).[20] [21] [22] [23] Much of the work on vegetation classification comes from European and North American ecologists, and they have fundamentally dissimilar approaches. In North America, vegetation types are based on a combination of the following criteria: climate pattern, establish habit, phenology and/or growth form, and dominant species. In the current US standard (adopted past the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC), and originally developed past UNESCO and The Nature Conservancy), the classification is hierarchical and incorporates the not-floristic criteria into the upper (nearly general) v levels and limited floristic criteria only into the lower (about specific) ii levels. In Europe, nomenclature frequently relies much more heavily, sometimes entirely, on floristic (species) composition alone, without explicit reference to climate, phenology or growth forms. It oftentimes emphasizes indicator or diagnostic species which may distinguish ane classification from another.

In the FGDC standard, the hierarchy levels, from nigh general to almost specific, are: organisation, form, subclass, group, formation, alliance, and association. The lowest level, or association, is thus the near precisely defined, and incorporates the names of the dominant one to three (unremarkably 2) species of a type. An instance of a vegetation blazon defined at the level of form might exist "Forest, canopy cover > 60%"; at the level of a formation every bit "Winter-rain, broad-leaved, evergreen, sclerophyllous, airtight-canopy wood"; at the level of alliance as "Arbutus menziesii woods"; and at the level of association as "Arbutus menziesii-Lithocarpus dense flora forest", referring to Pacific madrone-tanoak forests which occur in California and Oregon, Us. In do, the levels of the brotherhood and/or an association are the most often used, specially in vegetation mapping, just equally the Latin binomial is most frequently used in discussing particular species in taxonomy and in general communication.

Dynamics [edit]

Like all the biological systems, constitute communities are temporally and spatially dynamic; they change at all possible scales. Dynamism in vegetation is defined primarily as changes in species composition and/or vegetation structure.

Temporal dynamics [edit]

Temporally, a big number of processes or events tin can cause change, but for sake of simplicity, they can be categorized roughly as either sharp or gradual. Abrupt changes are generally referred to as disturbances; these include things like wildfires, high winds, landslides, floods, avalanches and the like. Their causes are usually external (exogenous) to the customs—they are natural processes occurring (mostly) independently of the natural processes of the community (such equally formation, growth, death, etc.). Such events can change vegetation structure and composition very quickly and for long fourth dimension periods, and they can do so over large areas. Very few ecosystems are without some type of disturbance equally a regular and recurring part of the long term organisation dynamic. Burn and air current disturbances are particularly common throughout many vegetation types worldwide. Fire is particularly potent because of its ability to destroy not merely living plants, but also the seeds, spores, and living meristems representing the potential side by side generation, and because of burn down'due south affect on animal populations, soil characteristics and other ecosystem elements and processes (for further discussion of this topic see fire ecology).

Temporal change at a slower step is ubiquitous; information technology comprises the field of ecological succession. Succession is the relatively gradual change in structure and taxonomic limerick that arises as the vegetation itself modifies diverse ecology variables over time, including low-cal, h2o and nutrient levels. These modifications alter the suite of species most adapted to grow, survive and reproduce in an area, causing floristic changes. These floristic changes contribute to structural changes that are inherent in found growth even in the absenteeism of species changes (particularly where plants have a large maximum size, i.e. copse), causing deadening and broadly predictable changes in the vegetation. Succession can be interrupted at whatever time by disturbance, setting the organization either dorsum to a previous country, or off on another trajectory altogether. Because of this, successional processes may or may not atomic number 82 to some static, final state. Moreover, accurately predicting the characteristics of such a country, even if it does ascend, is non always possible. In curt, vegetative communities are subject area to many variables that together set limits on the predictability of future weather condition.

Spatial dynamics [edit]

As a general rule, the larger an expanse under consideration, the more than likely the vegetation will be heterogeneous across it. Two chief factors are at piece of work. First, the temporal dynamics of disturbance and succession are increasingly unlikely to be in synchrony across any area as the size of that expanse increases. That is, different areas will be at dissimilar developmental stages due to different local histories, peculiarly their times since last major disturbance. This fact interacts with inherent environmental variability (e.g. in soils, climate, topography, etc.), which is too a role of area. Environmental variability constrains the suite of species that can occupy a given surface area, and the two factors together interact to create a mosaic of vegetation atmospheric condition across the landscape. Only in agricultural or horticultural systems does vegetation ever arroyo perfect uniformity. In natural systems, at that place is always heterogeneity, although its scale and intensity will vary widely..

See also [edit]

- Biocoenosis

- Biome

- Ecological succession

- Ecoregion

- Ecosystem

- Constitute cover

- Tropical vegetation

- Vegetation and slope stability

References [edit]

- ^ "Global Maps". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. eight May 2018. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved eight May 2018.

- ^ Burrows, Colin J. (1990). Processes of vegetation change. London: Unwin Hyman. p. 1. ISBN978-0045800131.

- ^ Introduction to California Plant Life; Robert Ornduff, Phyllis Grand. Faber, Todd Keeler-Wolf; 2003 ed.; p. 112

- ^ Thurmann, J. (1849). Essai de Phytostatique appliqué à la chaîne du Jura et aux contrées voisines. Berne: Jent et Gassmann, [i] Archived 2017-10-02 at the Wayback Car.

- ^ a b Martins, F. R. & Batalha, Chiliad. A. (2011). Formas de vida, espectro biológico de Raunkiaer e fisionomia da vegetação. In: Felfili, J. M., Eisenlohr, P. V.; Fiuza de Melo, M. K. R.; Andrade, L. A.; Meira Neto, J. A. A. (Org.). Fitossociologia no Brasil: métodos e estudos de caso. Vol. ane. Viçosa: Editora UFV. p. 44-85. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-08-25 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy equally title (link). Before version, 2003, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-27. Retrieved 2016-08-25 .{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ de Candolle, Augustin (1820). Essai Élémentaire de Géographie Botanique. In: Dictionnaire des sciences naturelles, Vol. xviii. Flevrault, Strasbourg, [2].

- ^ Lomolino, Thou. V., & Brownish, J. H. (2004). Foundations of biogeography: archetype papers with commentaries. University of Chicago Press, [3].

- ^ Coutinho, L. M. (2006). O conceito de bioma. Acta Bot. Bras. twenty(i): thirteen-23, Coutinho, Leopoldo Magno (2006). "O conceito de bioma". Acta Botanica Brasilica. 20: xiii–23. doi:x.1590/S0102-33062006000100002. .

- ^ Humboldt, A. von & Bonpland, A. 1805. Essai sur la geographie des plantes. Accompagné d'un tableau physique des régions équinoxiales fondé sur des mesures exécutées, depuis le dixiéme degré de latitude boréale jusqu'au dixiéme degré de latitude australe, pendant les années 1799, 1800, 1801, 1802 et 1803. Paris: Schöll, [iv] Archived 2018-05-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Humboldt, A. von & Bonpland, A. 1807. Ideen zu einer Geographie der Pflanzen, nebst einem Naturgemälde der Tropenländer. Bearbeitet und herausgegeben von dem Ersteren. Tübingen: Cotta; Paris: Schoell, [five] Archived 2017-11-07 at the Wayback Auto.

- ^ Grisebach, A. 1838. Über den Einfluß des Climas auf die Begrenzung der natürlichen Floren. Linnaea 12:159–200, [half-dozen] Archived 2017-11-07 at the Wayback Automobile.

- ^ Martius, C. F. P. von. 1824. Die Physiognomie des Pflanzenreiches in Brasilien. Eine Rede, gelesen in der am xiv. Febr. 1824 gehaltnen Sitzung der Königlichen Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. München, Lindauer, [vii] Archived 2016-10-12 at the Wayback Auto.

- ^ Ebach, Grand.C. (2015). Origins of biogeography. The role of biological classification in early plant and animate being geography. Dordrecht: Springer, p. 89, [8].

- ^ Beard J.S. (1978). The Physiognomic Arroyo. In: R. H. Whittaker (editor). Nomenclature of Found Communities, pp 33-64, [9].

- ^ Eiten, Chiliad. 1992. How names are used for vegetation. Journal of Vegetation Science three:419-424. link.

- ^ Walter, B. M. T. (2006). Fitofisionomias practise bioma Cerrado: síntese terminológica east relações florísticas. Doctoral dissertation, Universidade de Brasília, p. 10, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2016-08-26 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as championship (link). - ^ Rizzini, C.T. 1997. Tratado de fitogeografia practise Brasil: aspectos ecológicos, sociológicos e florísticos. two ed. Rio de Janeiro: Âmbito Cultural Edições, p. seven-eleven.

- ^ Cox, C. B., Moore, P.D. & Ladle, R. J. 2016. Biogeography: an ecological and evolutionary approach. 9th edition. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, p. 20, [10].

- ^ Wagner, H. & von Sydow, East. 1888. Sydow-Wagners methodischer Schulatlas. Gotha: Perthes, "Sydow-Wagners methodischer Schul-Atlas - Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek". Archived from the original on 2016-09-eleven. Retrieved 2016-08-30 . . 23th (last) ed., 1944, [11] Archived 2017-03-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ de Laubenfels, D. J. 1975. Mapping the Earth's Vegetation: Regionalization of Formation and Flora. Syracuse University Printing: Syracuse, NY.

- ^ Küchler, A.W. (1988). The classification of vegetation. In: Küchler, A.W., Zonneveld, I.S. (eds). Vegetation mapping. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, pp 67–80, [12].

- ^ Sharma, P. D. (2009). Environmental and Surroundings. Rastogi: Meerut, p. 140, [thirteen].

- ^ Mueller-Dombois, D. 1984. Classification and Mapping of Institute Communities: a Review with Accent on Tropical Vegetation. In: G. M. Woodwell (ed.) The Role of Terrestrial Vegetation in the Global Carbon Cycle: Measurement by Remote Sensing, J. Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 21-88, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-07-17. Retrieved 2016-09-04 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

Further reading [edit]

- Archibold, O. W. Ecology of World Vegetation. New York: Springer Publishing, 1994.

- Barbour, M. G. and W. D. Billings (editors). North American Terrestrial Vegetation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Barbour, M.G, J.H. Burk, and W.D. Pitts. "Terrestrial Plant Ecology". Menlo Park: Benjamin Cummings, 1987.

- Box, E. O. 1981. Macroclimate and Plant Forms: An Introduction to Predictive Modeling in Phytogeography. Tasks for Vegetation Science, vol. 1. The Hague: Dr. Westward. Junk BV. 258 pp., Macroclimate and Plant Forms: An Introduction to Predictive Modeling in Phytogeography.

- Breckle, South-W. Walter's Vegetation of the Globe. New York: Springer Publishing, 2002.

- Burrows, C. J. Processes of Vegetation Change. Oxford: Routledge Press, 1990.

- Ellenberg, H. 1988. Vegetation ecology of fundamental Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Vegetation Ecology of Central Europe.

- Feldmeyer-Christie, East., N. E. Zimmerman, and S. Ghosh. Modernistic Approaches In Vegetation Monitoring. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado, 2005.

- Gleason, H.A. 1926. The individualistic concept of the establish association. Message of the Torrey Botanical Club, 53:1-20.

- Grime, J.P. 1987. Found strategies and vegetation processes. Wiley Interscience, New York NY.

- Kabat, P., et al. (editors). Vegetation, Water, Humans and the Climate: A New Perspective on an Interactive System. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag 2004.

- MacArthur, R.H. and E. O. Wilson. The theory of Isle Biogeography. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1967

- Mueller-Dombois, D., and H. Ellenberg. Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1974. The Blackburn Press, 2003 (reprint).

- UNESCO. 1973. International Classification and Mapping of Vegetation. Series 6, Ecology and Conservation, Paris, [14].

- Van der Maarel, E. Vegetation Ecology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2004.

- Vankat, J. 50. The Natural Vegetation of North America. Krieger Publishing Co., 1992.

External links [edit]

Nomenclature [edit]

- Terrestrial Vegetation of the U.s. Volume I – The National Vegetation Classification System: Development, Status, and Applications Archived 2008-xi-22 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- Federal Geographic Data Committee Vegetation Subcommittee

- Vegetation Classification Standard [FGDC-STD-005, June 1997] (PDF)

- Classifying Vegetation Condition: Vegetation Assets States and Transitions (VAST)

[edit]

- Interactive world vegetation map by Howstuffworks

- USGS - NPS Vegetation Mapping Program

- Checklist of Online Vegetation and Institute Distribution Maps

- VEGETATION image processing and archiving eye at VITO

- Spot-VEGETATION program spider web page

Climate diagrams [edit]

- Climate Diagrams Explained

- ClimateDiagrams.com Provides climate diagrams for more than 3000 atmospheric condition stations and for dissimilar climate periods from all over the globe. Users can also create their own diagrams with their ain information.

- WBCS Worldwide Climate Diagrams

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vegetation

Posted by: brumfieldgince1938.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Geographic Term For A Plant And Animal Community Covering A Large Land Area"

Post a Comment